Minneapolis City Hall

1889-1905, 1971, 2007, 2017

PDF of the Minneapolis City Hall History

In 1886, Minneapolis was the fastest-growing city in the U.S. Its population between 1880 and 1885 grew from 46,000 to more than 219,000. In 1887, the legislature passed an act creating the “Board of Court House and City Hall Commissioners.” This act set forth a vision to build a Municipal Building, with an eye to the future, a joint City Hall/County Courthouse. This structure was to be built to accommodate a population growth of 500,000 and was to be able to house all the various city and county needs. This legislative act of March 1887 appointed a nine-member committee, authorized a $1,150,000 bond, and designated “block 77” as the chosen location for this new venture.

The site, Block 77, was part of the original town of Minneapolis and had been designated for public use. It was part of the Fort Snelling Military Reservation until an act of Congress in 1855 gave permission for the Government to convey title to Adelbert Harwell.

Harwell, together with Daniel Coolbaugh, began platting the original town of Minneapolis. In August 1855, Block 77 was sold to William Babbitt for $50.00. By the next year, June 1856, the northwest half of Block 77 was conveyed to the trustees of School District No. 1, Hennepin County for $2,500.00 to become the first public schoolhouse of the town of Minneapolis, west of the Mississippi River, “Union School.” The school’s large bell tower called children to school sounded fire alarms and pealed joyously whenever the Union Army was victorious in the Civil War. In 1865, The “Union School” burned and quickly was replaced by “Washington School” which remained in use until 1887 when it made way for the Municipal building.

Hennepin County Library

In 1889, the Minneapolis Tribune noted that “Minneapolis gives promise of having a hall of justice which will be pushed to completion without any of these prevailing irregularities of delay, jobbery, and bad faith, and without carrying down to future generations the taint of boodle and the crumbling evidences [sic] of bad architecture and worse construction.”

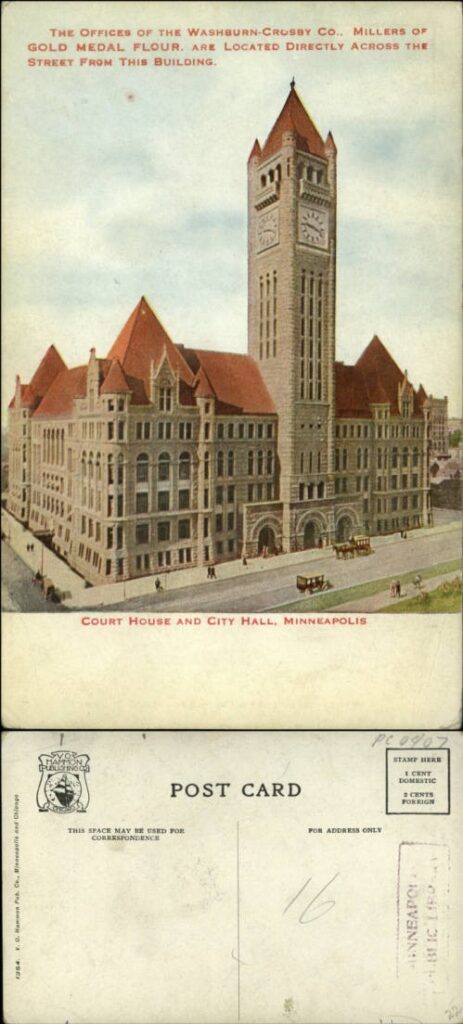

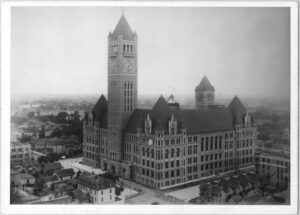

The City Hall/County Courthouse was constructed between 1889 and 1905, at a cost of more than $3,000,000. It was designed by Long and Kees (Masonic Temple and Lumber Exchange) in their interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque, with its design based on a courthouse in Pittsburgh. This style of architecture follows Henry Hobson Richardson, an influential architect of the Nineteenth Century. Richardson’s style was a blend of Romanesque, Gothic, and Syrian design, characterized by the use of massive surfaces, heavily worked stone, steep roofs, and windows with rounded arches.

The structure covers the entire city block bounded by Third and Fourth Avenues South and Fourth and Fifth Streets South. It is five stories in height and topped with a tower rising four hundred feet above the street. The tower is fifty feet square. Both the building and the tower are constructed of red/pink Ortonville granite. The building was the tallest building in Minneapolis until 1920 when the Foshay Tower was built. The building’s deed placed half the building belonging to Hennepin County (Fourth Avenue side) and the other half belonging to the City of Minneapolis (Third Avenue side).

The building’s tower has a clock face on all four sides which are twenty-three feet, four inches in diameter. It is the world’s largest four-faced chiming clock.

The clock tower also houses a carillon of bells, a multistory vault, and, for decades, a lookout point for visitors. Above the clock is the belfry where fifteen bells hang from wooden beams. Four times an hour, the bells chime over the city, with periodic special concerts.

The roof was originally heavily textured slate but has since been replaced by sheet copper. The base of the building is formed by huge blocks of stone, some weighing up to twenty-six tons, standing on bedrock forty-two feet below the surface. The building’s foundation is over seven feet thick.

The interior of the building is finished in a simple style. Quarter-sawn oak was used throughout the offices and courtrooms, and in the halls, there is marble wainscoting and tiled and mosaic floors. The most impressive interior element is the five-story light court. The southern wall and ceiling display elaborately designed stained glass. The court is surrounded on three sides by arcaded stories linked by filigree iron stairs. Although the interior has been modernized, it retains its design integrity.

In the center of the courtyard is a sculpture: Mississippi-Father of Waters. This statue is the work of the American sculptor Larkin Mead. It was created during his residence in Florence, Italy. Carved from the largest single block of marble taken from the Carrara quarries in Italy, it was presented to the city in 1904, as a gift from the Minneapolis Journal and twelve generous Minneapolis citizens.

Larkin Mead was originally commissioned to do this representation of the Mississippi “Father of Waters” for a citizen of New Orleans, but the agreement failed to materialize, and the carving was halted.

In 1902, a Minneapolis citizen paid a visit to Mead’s studio in Florence, and when he saw the uncompleted statue, he was determined to bring it to Minneapolis. The statue features the journey of the Mississippi River from the headwaters in Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. The old man of the river with a long wavy beard, and a wreath upon his head, is reclining on a Native American blanket with his back braced by the paddlewheel of a river boat. He holds a cornstalk, while surrounded by a fish net, an alligator, and a large tortoise. His big toe is so tempting that over the years the toe has a shining brightness from being rubbed.

It took 21 years from the time of the legislative act in 1887 to the building’s completion in 1909. According to the Minneapolis Tribune article of July 28, 1889, the municipal building was the first “elastic” building in the United States, one in which the arrangement of offices may be changed at any time with floors supported independently of partitions.

It took 21 years from the time of the legislative act in 1887 to the building’s completion in 1909. According to the Minneapolis Tribune article of July 28, 1889, the municipal building was the first “elastic” building in the United States, one in which the arrangement of offices may be changed at any time with floors supported independently of partitions.

Initially, there was so much room in this massive building that space was rented out for a variety of non-governmental uses. A chicken hatchery on the second floor, a blacksmith shop, and a horse stable used by the fire department all found their way into the building. Having extra space, however, was short-lived. By 1940, the municipal building was overcrowded and required the additional space now provided by a 24-floor government center.

Cedric Adams wrote in the Minneapolis Tribune, April 1954, “Back in 1887 and known as the municipal building there were plenty of squawkers who bellyached about erecting a three-million-dollar granite structure. Some called it as silly as digging a ship canal from Minneapolis to Duluth” He added that, “Local papers linked it to a style referred to as ‘Norman’, the English name for the Romanesque style introduced from France during the Norman Conquest. Its crude surfaces and simplicity of the form spoke of northern vigor and hardihood. The use of this building style was based on collaboration between arts such as stonecutting and ironmongery and was a clear outgrowth of the late 19th-century reaction to the erosion of the human environment and loss of individual identity by the Industrial Revolution.”

In 1971, the bells were fully automated and are now played on an electric keyboard in the atrium of the rotunda near the Fourth Street entrance. In 2007, the clock’s hands were refurbished, and the dial gears were rebuilt with a master clock unit installed to automatically set the time by GPS signal. In 2017, the clock faces were completely restored to their original glass appearance with backlighting.

City Hall continues to be one of the most impressive nineteenth-century public buildings in the state. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 and was designated as a Heritage Preservation Building by the City of Minneapolis in 1977. There are no skyways connecting City Hall with other downtown buildings. Alterations are not allowed for buildings on the National Registry. Instead, pedestrian tunnels connect the building to the Hennepin County Government Center and the U.S. Courthouse.