Dorsey Sporting House

1890, 1920, 1996

PDF of Dorsey Sporting House History

Built in 1890, this Romanesque Revival building is the last of the brothels built for that purpose in the newly established Eleventh Avenue red-light district of Minneapolis. The red-light district in another area of downtown was being closed, necessitating the move by Dorsey and others to Eleventh Avenue South. The building was built for and run by Ida Dorsey, a successful African American entrepreneur.

Ida Dorsey was born Ida Mary Callahan in Kentucky on March 7, 1866. Little is known about her life prior to moving to the Twin Cities, although it is assumed that her mother had been enslaved and her father was white. By 1886 she had changed her name to Dorsey and had established herself as a madam in St. Paul.

Ida Dorsey soon proved herself to be one of the Twin Cities’ most successful madams, running multiple brothels between the 1880s and the 1910s. As a woman of color in an industry dominated by white women, she was an adept entrepreneur and real estate owner.

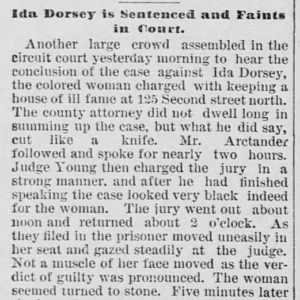

Prior to opening her business on Eleventh Avenue, Dorsey had been sentenced to ninety days in Stillwater State Prison in 1886 for running a house of prostitution and selling liquor without a license. Although other madams were caught in the raid with Dorsey, they were white and received fines. Dorsey was one of two madams put in prison during the decade.

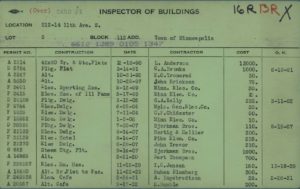

Dorsey was one of the first to populate the new Eleventh Avenue Red Light District, a shift planned and established by the city’s madams. An immigrant community had lived in the area but lacked the political influence to resist the building of a new red-light district. The building’s purpose was not hidden. “Sporting House,” as a term of use, was listed on a number of city permits for such businesses. The permits for Ida Dorsey’s building reference both “Sporting Hse” and “Hse of Ill Fame.” Dorsey built the new bordello for $12,000 and spent another $15,000 on furnishings.

The geographic containment of the red-light districts demonstrated an agreement between city officials and the madams: vice was sequestered, while the madams became some of the biggest property owners in the area. The new red-light neighborhood had obvious logistical advantages: it was within a Liquor Patrol District (liquor was not allowed to be sold outside of designated areas), close to flour mills and railroads that would generate walk-in customers, and on the Washington Avenue streetcar line.

Like other brothels in the city, the land at 212 Eleventh Avenue South transferred through arrangements to conceal actual ownership. Andrew Haugan (who had served on the city council) and his wife, Louise, sold the property to Carolina Anderson, who took out a building permit with the city for a three-story, $12,000 apartment structure. Anderson’s husband, Zacharias, became the general contractor. Another party, John L. Anderson, owned the building in trust for Carolina Anderson and Ida Dorsey. A former alderman and park commissioner supplied the lumber. The final transfer occurred in 1906 when Dorsey gained the title, using the name Callahan.

Dorsey sent announcements of the opening of her establishment to many, including to pastors who were primarily interested in closing her business. Due to the influence of her clients, Dorsey was not subject to frequent raids at her new location.

Dorsey had a publicly acknowledged affair with Carleton Pillsbury, the nephew of flour miller Charles A. Pillsbury and the grandson of Minneapolis mayor George A. Pillsbury. After Pillsbury died, she would occasionally refer to herself as Mrs. Ida Pillsbury.

In 1907, opposition to the toleration of prostitution increased in Minneapolis. Dorsey was subject to a vice raid and arrested in 1911.

On March 7, 1913, Dorsey relocated her brothel to St. Paul.

After the Eleventh Avenue brothel was shut down, Bert Thompson, another African American entrepreneur, moved his barber business to the building and in 1920 received a permit for alterations of the building into a rooming house for the many African American porters in the area. He later added a café and gradually added permits for tobacco and alcohol.

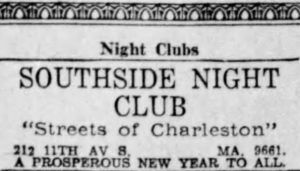

Eventually, the space became the Southside Night Club.

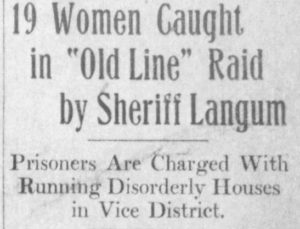

When Prohibition ended, legal bars were opened again in Minneapolis. The legal bars had strict opening and closing laws. Prohibition-era speakeasies could be open as late as 7 am. Normal closing hours for illegal bars, such as the Southside Night Club, continued after the closing time set for legally run bars.

In 1935, an article in the Minneapolis Spokesman reported that an order had been issued requiring nightclub owners to cater to only one race. In the article, the owner of the Southside Night Club was listed as Bert “Dutch” Thompson.

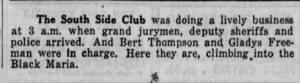

The club was in the news again in January of 1938, when Thompson and two employees were jailed following a raid at the club. Thompson was charged with “keeping a disorderly house,” and employees, Nick Carter and Gladys Freeman, were charged with being “found in” a disorderly house.

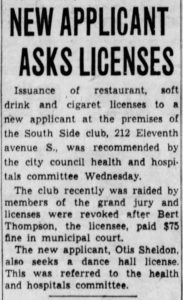

The January 6, 1938, Minneapolis Star featured a photo of Thompson and Freeman getting into a Black Maria (reference to a closed police van). Thompson was found guilty of operating a “disorderly house,” and the club’s licenses were revoked for four weeks, putting twenty-two employees out of work.

The license was transferred to Otis Sheldon.

Sheldon’s business was not successful, and by 1939, the famed Southside Night Club was no longer in operation.

In 1948, 212 Eleventh Avenue South was home to Miles Manufacturing, an upholstery business.

In the 1950s, 212 Eleventh Avenue South housed New Hope Center, a homeless shelter and drug and recovery program serving men, women, and mothers with children.

In the 1950s, Manor House, a wholesale furniture store, also occupied 212 Eleventh Avenue South. Manor House served five hundred Upper Midwest furniture dealers who referred customers to the business.

A Minneapolis Star Tribune article on September 27, 1959, reported that Manor House was founded eight years previously on the Eleventh Avenue site. Manor House had expanded its operations from one-third of the building to the full 15,000 square feet. Because it had outgrown the space, the business was expanding elsewhere.

In the mid-1990s a new owner, Robert Leonard, renovated 212 Eleventh Avenue South into its current iteration of apartments and small businesses.

As the Mill District developed into a revitalized mixed-use neighborhood, many buildings were torn down to make room for new condominium buildings. It was at this time that an agreement was made to save 212 Eleventh Avenue South. The Bridgewater Condominiums were built around this historic Minneapolis building. Ida Dorsey’s Sporting House continues to quietly provide shelter and commerce in the Mill District of Minneapolis.